Not everyone realizes this, but we’re currently living through a stunning revolution in audio production. And it’s something at the forefront of my mind as I sit down to prep for a lengthy and informative interview with Michael Micha, whose work at Abandoned Studios has been just as innovative to my ear as any of the astounding local and regional artists we’ve talked about here at Parlor City Sound.

We’re seeing incredible DIY home recording projects garnering professional-grade results, like the recent single by Binghamton pop artist Amoreena. The growing popularity of digital audio workstations and the influx of budget-conscious, high-quality recording gear has made audio production far more accessible to everyday, working-class musicians.

That DIY ethos is slowly but surely creeping into those big blockbuster AAA studios who, in this modern all-things-digital age, are struggling to carve out unique sonic profiles that differentiate them from their big-budget competitors. Those gargantuan zillion-dollar recording studios simply don’t stand out like they once did. They’re not as groundbreaking, and they’re less influential to young, aspiring engineers. It’s more difficult now to listen to a AAA recording and identify a unique sonic signature.

Of course, DIY recording isn’t for everyone. If the steep learning curve doesn’t turn you off, the budget considerations might. And artists creating professional results in a home studio, like the aforementioned Amoreena, are a rarity. So the vast majority of recording artists will still want to find a professional recording studio to work with on their bigger projects. And if you’re looking for a recording studio that breaks away from that mainstream vacuum-sealed sound, it’s the smaller studios leading that charge of sonic character today. And that’s where Michael Micha and Abandoned Studios enter the chat.

Abandoned Studios: an award-winning engineer you can actually afford to work with

The recordings coming out of Abandoned Studios stand out in big ways when you listen to them. That’s partly the result of the space itself—it’s located within an old spool manufacturing factory. But it also comes from owner Michael Micha, an audio engineer with a deep appreciation for that sonic character I mentioned a bit ago.

Micha, as he’s known to most, is surprisingly approachable and humble, despite having what I can only reasonably describe as monolithic talent. Even winning an Emmy for his work on the 2022 season of the popular WSKG show Expressions hasn’t shaken his personality. And when you couple that easy, ego-free nature with Abandoned Studios’ astonishingly affordable rates and the standout sound of its space, you end up with a top-class recording facility helmed by an award-winning engineer you can actually afford to work with.

Whether you’re a musician looking to step into a professional recording space or a DIYer hoping to learn from a noteworthy local engineer, we wanted to make sure this interview was as valuable to you as possible. So grab a snack and kick back somewhere comfortable as we delve into our lengthy but insightful interview with Michael Micha at Abandoned Studios.

Let’s start with the classic chicken and egg question. Did you start out as a drummer and then evolve into the production end? Were the engineering aspirations there before you picked up the sticks?

Well if we’re going back to the beginning it starts with me playing guitar. A couple friends were playing music together and I showed interest, so my parents bought me a guitar. That was in tenth grade, by my senior year I wasn’t playing any sports, I was playing music any time I wasn’t in school. So performing music definitely came first. I became interested in production after my musical tastes started to venture into underground music.

I get to ask musicians about their influences pretty regularly, and we’ll get into that in a moment. But this is the first time in a Parlor City Sound interview where I get to geek out over sound engineering and production. So who are your influences as a producer?

Oooh, I love this question! I’ve found that I’m more influenced by engineers than producers. Engineers being the people that set up the mics, that have their hands on the gear, producers being the people that help make decisions about song structure and lyrics, generally speaking.

I like taking engineering techniques from lots of different people and time periods. I would say my influence is more based on how certain engineers approach recording. The first that comes to mind is Steve Albini, his approach is very hands-off. Not wanting to insert himself or his tastes into a band’s sound. That strikes a chord with me.

Bands that come into the studio are also music lovers, they already have a vision of what they want their songs to sound like. It’s not my place to tell them they should sound like [blank]. Its my role to take what they are telling me about their influences, about how their experiences have shaped their music and try to deliver their vision, not my vision.

A lot of the audio engineers from the 60s and 70s were technically-minded people, they took the knowledge of audio, microphones, preamps, et cetera, and used that knowledge to make a decision of what equipment to use in a certain situation to yield a desired result. They were not making decisions about song structure, about lyrics or about a performance. So a lot of techniques like the Glyn Johns stereo technique, the Decca tree technique, the mid-side technique or the Blumlein technique. These ways of setting up microphones were created by technically minded people that were trying to achieve a desired sound. The place where creativity and the technical application of sound and audio cross is where I get very very excited to work.

Not to blow smoke or anything, but your drumming is stellar and consistently impresses the hell out of me. So this is a great chance to ask that other ‘influences’ question. Who makes that list for you personally?

Wow. That’s so sweet. I honestly don’t think that I am a great drummer—I think I’m an okay drummer. I started much later than most drummers and I don’t have any professional training. I started playing drums about nine years ago … I’m 38. I don’t know that my influences really show in my playing because I’m influenced by extremely talented, and in some cases prolific, drummers. Some of those people are Damon Che (Don Caballero), Blake Fleming (Dazzling Killmen/ Laddio Bolocko/ Mars Volta), Jon Theodore (The Mars Volta/ Queens of the Stone Age), Elvin Jones. Out of that list I think Damon Che takes the cake as most influential, I’ve never heard any drummer play like he does. It’s unreal.

It’s going to start looking like a vape shop in here from that aforementioned smoke, but I have to hurl a little more praise your way. I’ve been quite literally stunned by that gorgeous analog sound you’re getting at Abandoned Studios. And these days, with everything we can do in a DAW, it’s not always easy to tell if someone is tracking or doing mixdowns on tape or if they’re using plugins, or some combination thereof. How are you getting that distinct sound?

I have dabbled with tape, using it for mix downs, using tape machines for a tape delay. In general there is something special about analog equipment, something about the alchemic nature of it, specifically the way that recording to tape forces you to make decisions throughout the process. Decisions you don’t have to make when recording in a DAW. All of that I absolutely love about tape. Having said that, I am not a purist. At the end of the day it’s about what is coming out of the listener’s speakers, that’s it.

I made a decision about a year ago that not enough bands that came to my studio were requesting tape to be used, and a lot of them didn’t want to pay extra for the cost of the tape. So I decided to sell my tape machine and use the money from that on microphones and preamps. I’d say the analog sound that I get is due to the mixers, preamps, and microphones that I use. As well as some of the miking techniques, I don’t think it’s necessarily one specific thing.

I’m going to try and not nerd out over the engineering stuff too much. But in terms of hardware, could you walk me through the key points in your signal flow a little? Just the big ticket items I mean, like mixers and primary preamps and interfaces, et cetera.

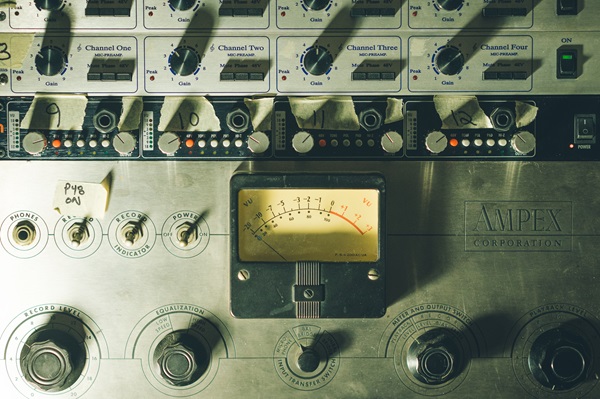

Haha, absolutely. The main mixer I use is a 16-channel Yamaha M1516, made in 1982. Often referred to as a ‘Japa-Neve’ because it was basically Yamaha’s response to the Neve consoles. It obviously doesn’t sound exactly like a Neve because it’s not a Neve. It does have a fantastic Yamaha-manufactured op-amp, the same op-amp used in the Yamaha PM2000. I modified it so that I could have direct outputs for each channel. I installed sixteen CAPI hand wound transformers, one for each channel, so it has transformer-balanced outputs now as well. I also re-capped the power supply and each channel. The next mod I have planned, if I have the down time to get it done, is to modify the EQs on each channel to make them a bit more musical. In addition to the 16-channel Yamaha mixer I also have several racked preamps. I have eight Sytek preamps—same engineer/ circuit from the Neotek consoles—I have a WA412 which is a four-channel Warm Audio recreation of API preamps, I have a two-channel Warm Audio tube preamp and an old Ampex 350 preamp. I have a handful of compressors/limiters, I plan to add a few rack EQ units soon.

I’m also a drummer, so of course I want to ask you about drum miking. I don’t think most people really appreciate just how many challenges are involved in miking drums. Half of the channels on my mixer are basically an office block for the Sennheiser corporation. It’s all drum microphones at that end of the street. So I’d love to know more about your preferred drum miking techniques. Do you mic everything, or go for a more minimal approach?

I always start by asking the band a few questions. I have them send me music that influences their music, as well as music that they enjoy the sonic qualities of. That helps give me a direction to go in. I’m a big supporter of there being no rules. Having said that, generally speaking, if I’m recording a metal band then I am setting up spot mics for all of the drum elements. Either an A/B spaced pair or X/Y overhead setup, mic on the hi-hat, mic on the ride, inside kick for the attack and a large diaphragm condenser on the outside for the meat. Snare gets a top mic, usually three to four inches from the batter head—I only use a snare under if I feel like I need it, but it’s rare—either an SM57 or a small diaphragm condenser.

With metal I usually use an AKG 414 on each tom. The room mics [are] where I like to have a lot of fun. I always leave a large diaphragm WA-87 condenser plugged into channel sixteen on my Yamaha mixer, that mic is all the way in the back of the room facing the back wall. I have used several different stereo room techniques, the Albini technique was a regular for a long time. Two small diaphragm condenser mics, with omni capsules, taped directly onto the floor equidistant from the kick drum and each other. Creating a triangle between the two mics and the kick drum. Delay each of those mics by a few milliseconds, usually between fifteen and thirty milliseconds.

I’ve miked up a wall in my studio that is about twenty-five to thirty feet away from the drums with small diaphragm condenser mics with an omni capsule, essentially making a boundary mic with them. I’ve also used large ribbon mics about twenty feet in front of the kit in an A/B spaced pair, sometimes behind a barrier, sometimes not. For any bands that aren’t metal bands the close mics and the stereo overheads change up. I like using a modified Glyn Johns technique with ribbon mics, one overhead, one looking laterally across the floor tom pointed at the snare, one kick drum mic out in front of the kit all equidistant from either snare or kick.

I often like using a bone mic on drummers not in metal bands, usually that is an EV 635L, just above the kick pointed at the drummers crotch. Toms I usually go for Sennheiser 421s or the AKG 414s. If the band is looking for something specific I tailor my setup to their request. So I’ve done more minimalist approaches as well, those scenarios I like to make sure the drummer and band understand that the sound that is recorded is, for the most part, what it will sound like as an end result. Using less mics means less control in post production but can yield very unique, exciting drum sounds.

Also Read: How to record drums in a home recording studio

There’s this very stunning room sound you’re capturing. With Abandoned Studios being built within the innards of an old factory, I imagine the location itself presented some challenges on that front. Or did the space just sound really good out of the gate?

As far as acoustics go, I am incredibly spoiled. The space sounded fantastic the first day I walked in there. It’s a near perfect blend of dryness and reverb. Fifteen-foot arched ceilings, insulated ceilings, wood floors and all of the walls have these thick fabric curtains, except for the front and back wall that are bare sheetrock. So I didn’t need to treat the acoustics of the room, really at all. But what I did need to do was build gobos, so that I can isolate amps and instruments but also to get a tighter sound when needed. So I have two seven-foot tall, five-inch deep movable walls. One side with open rockwool insulation and the other side a flat wooden surface, for absorption or reflection, depending on what I want. And I also have two five-foot tall, twelve-inch deep moveable walls for use with bass-heavy instruments. I also have a DIY iso booth, that I built, to isolate amps and also record vocals within.

Abandoned Studios isn’t just audibly great, but aesthetically as well. It’s almost like a highly functional art installation. How did you end up getting to build a recording studio in that space?

In the late 1800s it was built and used for spool manufacturing, under the name Lestershire Spool Manufacturing. Roughly twenty years ago the building was purchased by its current owner, Don DeMauro, who is an incredible artist. He started an art gallery on the first floor, Spool Contemporary Artspace. My wife and I were invited to create an art installation for one of their shows, that’s how we met Don. After that we were invited to be on the board for the gallery and began volunteering for Spool. I mentioned to Don that I was looking to start a recording studio and needed a space, he took me up to the second floor and I was blown away.

My connection to the space I’m in is sort of serendipitous, I grew up about four blocks down from the building, I would walk by it often on my way to Fat Cat Books. Later in my life I saw several shows in the same room, mostly punk shows. I didn’t learn this until I moved into the space but my godfather, Burt Stasko, ran a computer chip company out of the same space. What was his office is now my mixing room. The space has a very welcoming, creative energy that almost every band notices without being prompted. Again, I am incredibly lucky and spoiled to use this space that has been part of the local music scene and my life for a long time. I can’t explain how appreciative I am for every minute I get to spend creating or recording music in it.

The vocals you capture are always excellent. That’s one of the first things I noticed when I reviewed the Alyssa Crosby and Grown Ups collaboration ‘Loved So Bad’, and again, when I heard Bob Rodgers’ singing with Neo Politans on ‘American Harmony’, I thought ‘damn, this is spot on.’ I’ve wondered what they’re singing into. There’s a lot of warmth and clarity there, and those two ideas don’t always share sentences together.

Thank you! Vocals are actually the instrument I feel I struggle with the most, so that is great to hear. My new favorite preamp for vocals has been my Warm Audio tube preamp, it’s got a lot of range. It can be as clear and transparent as a tube pre can be, all the way to full-saturated dirty overdriven tube sounds and everywhere in between. It’s a very versatile preamp. Alyssa’s vocals on Loved So Bad were recorded with an AEA R84 ribbon mic going into the WA tube pre, slightly saturated for a little break up. Bob, from the Neo Politans, wanted to double track his vocals. So for that I used two different mics, I find that with double tracked vocals if you use the same microphone the character isn’t different enough between the two vocal tracks. So with Bob I used an SM7B and a tube condenser mic similar to an AKG C12—it’s an Apex 460 gutted with a new tube, mic element, capacitors and transistors.

Let’s pivot a little and answer a few questions music acts might have when considering Abandoned Studios for their next project. What services are on offer at Abandoned Studios?

I offer tracking, mixing and mastering services. In any combination or individually as requested.

We should ask the million-dollar question too, no pun intended of course. How are your rates structured? How much does a typical recording session cost at Abandoned Studios?

I never want money to come between a band wanting to record their music. That happened to me early on when playing music and I know there are so many bands that didn’t have the funds to record their music, and now that music is lost. So as long as I have the opportunity to work with bands on the cost I will.

My rates are $35 per hour for recording and $25 per hour for mixing. To give you an idea of what that is practically, a band that wants to record a ten-song album, they can usually get that done in two eight-hour sessions. Sometimes an additional four-hour session is necessary for vocals or overdubs. So for $560 to $700 a band can record a full length album with me. Then I put together a rough mix for the band and send them those rough mixes, they make notes, then we get back together at the studio to address those notes.

What would you say are the key selling points for Abandoned Studios? What is it that makes your studio stand out? Apart from all of that gushing I did earlier, I mean.

It’s probably not the best answer, but I think a major selling point for a lot of bands is the comfort of recording with me in this space. I’ve had so many bands tell me that they’ve never had such a fun, easy time recording music with anybody. My approach to recording bands has always been to get the band feeling as comfortable as they possibly can before I hit record. I want that band to feel like they’re just at another band rehearsal, to forget that I’m even there. The best recording I can provide a band starts with them feeling confident and comfortable with their performance and I think I do a great job at getting a band feeling comfortable in the live room.

What’s the litmus for a band to say ‘okay, we’re ready to track at Abandoned Studios.’ How does a band know they’re ready to step into a professional recording space?

I would say when that band has their material rehearsed so well that they barely even need to think about it. They should be almost bored of playing their material so many times. That way when they come in to record they won’t be struggling with performance issues, that will allow more time to make sonic choices.

I remember feeling super intimidated going into a professional recording studio for the first time, when I was maybe fifteen or sixteen years old. That was a lot. I couldn’t follow the click track to save my life. Honestly, I still can’t all these years later. How do you keep an inexperienced client relaxed and focused? What advice would you offer someone stepping into a professional studio for the very first time?

Yeah, I also struggle with a click. I’m not a trained drummer so a click is like being chained to a boat anchor. I often tell bands that they’re free to bring in a friend or two, I’ve found this helps them relax. But mostly I just try to be as friendly and accommodating as I can be. Joke with them, talk about what music they’ve been listening to recently, what shows they’ve been playing, if they’ve seen any good shows in the past year or so, talk gear with them. If I can get them comfortable communicating with me the entire process is going to be a lot more fruitful.

I think a good place to end on would be to discuss the prevalence of at-home recording today. A lot of musicians are building amateur setups at home for making demos and other small projects. Is there any advice you’d offer those who take this DIY approach? Is there a particular project size where they’d be best off calling Abandoned Studios versus attempting to do it at home?

I come from a very strong DIY ethos. I was taught how to solder by a professor in Oneonta when I was going to school, and that small act was revolutionary for me. I now had the foundation to fix or make my own cables, soon I was opening up audio equipment to learn how it functioned, I was modifying mixers and preamps and mics, I was circuit bending. I fully support the DIY ethos, I think it’s an incredibly freeing mindset.

Recently I’ve been privileged to be able to afford to pay professionals to do things instead of attempting to do them myself. For example, I was in need of some cable trees to hang my many cables. I was using a coat tree for a long time and I could’ve probably created something that would’ve worked. Sessions had been picking up quite a bit so I decided to commission a friend of mine, Derek Nelson, to make some cable trees for me. He went above and beyond, he used metal from an old jail in Owego that was the same time period as the building I’m in, late 1800s. He carved out the Abandoned Studios logo, the Vacanti mouse, into the base of the cable trees, they’re about ten feet tall and he made them so they can be disassembled and they’re also lamps! They’re practical pieces of art and I absolutely love them. I could’ve never done anything even close to that.

Again, I am not a purist. I will DIY till I die, but I won’t DIY or die. I want to support the talented people that I know by supporting their craft or art. So, in short, if you start a home recording setup and feel like there’s some kind of magic occurring, like you’ve never been so excited to do anything before, then you continue to pursue recording because it could very well become your outlet, craft, art. But if you have a home recording setup because you want people to hear your music, then I would suggest to at least reach out to a recording studio and just have a conversation about what that process would be like.

How to Contact Abandoned Studios

Music acts looking to record with Abandoned Studios can reach Michael Micha via email, and be sure to check out their official website too!